Analyzing Data with Python

# # widen notebook cells

# from IPython.core.display import display, HTML

# display(HTML("<style>.container { width:95% !important; }</style>"))

The process of converting data from the initial format to a format that may be better for analysis.

# import libraries

import pandas as pd

# data source

filename = "https://s3-api.us-geo.objectstorage.softlayer.net/cf-courses-data/CognitiveClass/DA0101EN/auto.csv"

# headers

headers = ["symboling","normalized-losses","make","fuel-type","aspiration", "num-of-doors","body-style","drive-wheels","engine-location","wheel-base",

"length","width","height","curb-weight","engine-type","num-of-cylinders", "engine-size","fuel-system","bore","stroke","compression-ratio",

"horsepower","peak-rpm","city-mpg","highway-mpg","price"]

# read in the data set

df = pd.read_csv(filename, names = headers)

# see what the data set looks like

df.head()

i. Identify Missing Values

# import libraries

import numpy as np

# replace "?" with NaN

df.replace("?", np.nan, inplace = True)

# Evaluating for Missing Data using either .isnull() or .notnull()

missing_data = df.isnull()

missing_data.head()

ii. Deal with Missing Values

Options

1. Drop data

Example: "price" -- Any data entry without price data is essentially useless as it cannot be used for prediction

# drop all rows that do not have price data

df.dropna(subset=["price"], axis=0, inplace=True)

# reset index, because we droped two rows

df.reset_index(drop=True, inplace=True)

df.head()

2. Replace data -- less accurate since we replace w/ a guess

Example: "normalized-losses", "stroke", "bore", "horsepower", "peak-rpm"

# Calculate the average of the column

avg_norm_loss = df["normalized-losses"].astype("float").mean(axis=0)

avg_stroke = df["stroke"].astype("float").mean(axis = 0)

avg_bore = df['bore'].astype('float').mean(axis=0)

avg_horsepower = df['horsepower'].astype('float').mean(axis=0)

avg_peakrpm = df['peak-rpm'].astype('float').mean(axis=0)

# Replace "NaN" by mean value in "normalized-losses" column

df["normalized-losses"].replace(np.nan, avg_norm_loss, inplace=True)

df["stroke"].replace(np.nan, avg_stroke, inplace = True)

df["bore"].replace(np.nan, avg_bore, inplace=True)

df['horsepower'].replace(np.nan, avg_horsepower, inplace=True)

df['peak-rpm'].replace(np.nan, avg_peakrpm, inplace=True)

Example: "num-of-doors" -- Like all noncategorical variables there isn't an average fuel type, for example. 84% of sedans have four doors. Since four doors is most frequent, it is most likely to occur

# calculate the most common value in a particular column

mcv = df['num-of-doors'].value_counts().idxmax()

# replace the missing 'num-of-doors' values with the most frequent

df["num-of-doors"].replace(np.nan,mcv, inplace=True)

iii. Correct Data Format

.dtype()to check the data type.astype()to change the data type

# df.describe()

# df.describe(include = "all")

# df.inf0

# df.dtypes

# Convert data types to proper format

df[["bore", "stroke"]] = df[["bore", "stroke"]].astype("float")

df[["normalized-losses"]] = df[["normalized-losses"]].astype("int")

df[["price"]] = df[["price"]].astype("float")

df[["peak-rpm"]] = df[["peak-rpm"]].astype("float")

df.dtypes

iv. Data Standardization

Standardization is the process of transforming data into a common format which allows the researcher to make meaningful comparisons.

Example: In our dataset, the fuel consumption columns "city-mpg" and "highway-mpg" are represented by mpg (miles per gallon) unit. Assume we are developing an application in a country that accept the fuel consumption with the L/100km standard

We would need to transform mpg to L/100km:

L/100km = 235 / mpg

# Convert mpg to L/100km

df['city-L/100km'] = 235/df["city-mpg"]

# transform mpg to L/100km in the column of "highway-mpg"

df["highway-mpg"] = 235/df["highway-mpg"]

# change the name of the column from "highway-mpg" to "highway-L/100km"

df.rename(columns={'highway-mpg':'highway-L/100km'}, inplace=True)

# check your transformed data

df.head()

v. Data Normalization

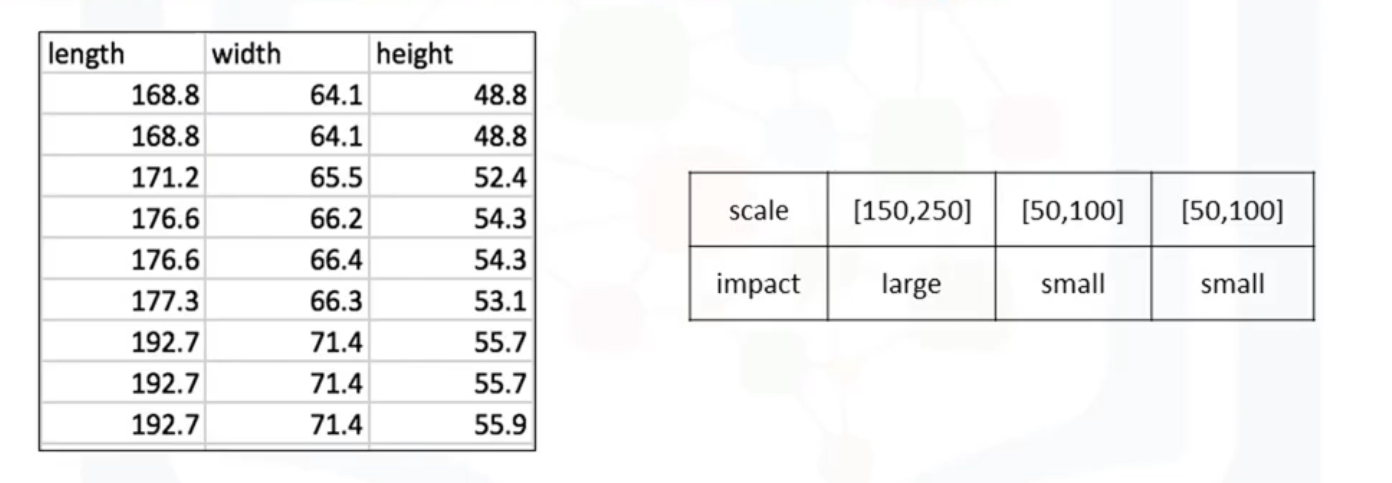

Different columns of numerical data may have very different ranges and direct comparison is often not meaningful. Normalization is a way to bring all data into a similar range for more useful comparison. Eg. In the used car data set, the feature "length" ranges from 150-250, while the features "width" and "height" range from 50-100. We could normalize these variables so that the range of the values is consistent.

Methods of Normalizing Data

- Simple Feature Scaling $$ x_{new} = \frac{x_{old}}{x_{max}} $$ Divide each value by the maximum value for that feature. New values range between zero and one.

df["length"] = df["length"]/df["length"].max()

- Min-Max $$ x_{new} = \frac{x_{old} - x_{min}}{x_{max} - x_{min}} $$ Min-Max takes each value X_old subtract it from the minimum value of that feature, then divides by the range of that feature. Again, new values range between 0 and 1

df["length"] = (df["length"] - df["length"].min())/ (df["length"].max() - df["length"].min())

- Z-Score or Standard Score $$x_{new} = \frac{x_{old} - \mu }{\sigma}$$ For each value you subtract mu (the average of the feature) and then divide by the standard deviation sigma. New values hover around zero, and typically range between negative three and positive three but can be higher or lower.

df["length"] = (df["length"] - df["length"].mean())/df["length"].std()

vi. Binning

Binning is a process of transforming continuous numerical variables into discrete categorical 'bins', for grouped analysis. For example, you can bin “age” into [0 to 5], [6 to 10], [11 to 15] and so on.

In our dataset, "horsepower" is a real valued variable ranging from 48 to 288, it has 57 unique values. What if we only care about the price difference between cars with high horsepower, medium horsepower, and little horsepower (3 types)? Can we rearrange them into three ‘bins' to simplify analysis?

# Convert data to correct format

df["horsepower"]= df["horsepower"].astype(int, copy=True)

# plot the histogram of horspower to see what the distribution of horsepower looks like

from matplotlib import pyplot

pyplot.hist(df["horsepower"])

# set x/y labels and plot title

pyplot.xlabel("horsepower")

pyplot.ylabel("count")

pyplot.title("horsepower bins")

# use numpy's linspace() functioin to get 3 bins of equal size bandwidth

bins = np.linspace(min(df["horsepower"]), max(df["horsepower"]), 4)

# set group names

group_names = ['Low', 'Medium', 'High']

# apply the function "cut" to determine what each value of "df['horsepower']" belongs to

df['horsepower-binned'] = pd.cut(df['horsepower'], bins, labels=group_names, include_lowest=True )

df[['horsepower','horsepower-binned']].head(5)

# draw historgram of attribute "horsepower" with bins = 3

pyplot.hist(df["horsepower"], bins = 3)

# set x/y labels and plot title

pyplot.xlabel("horsepower")

pyplot.ylabel("count")

pyplot.title("horsepower bins")

vii. Indicator variable

An indicator variable (or dummy variable) is a numerical variable used to label categories. They are called 'dummies' because the numbers themselves don't have inherent meaning. Indicator variables are used so we can use categorical variables for regression analysis in the later modules. Example:We see the column "fuel-type" has two unique values, "gas" or "diesel". Regression doesn't understand words, only numbers. To use this attribute in regression analysis, we convert "fuel-type" into indicator variables

# get indicator variables and assign it to data frame "dummy_variable_1"

dummy_variable_1 = pd.get_dummies(df["fuel-type"])

# change column names for clarity

dummy_variable_1.rename(columns={'fuel-type-diesel':'gas', 'fuel-type-diesel':'diesel'}, inplace=True)

# merge data frame "df" and "dummy_variable_1"

df = pd.concat([df, dummy_variable_1], axis=1)

# drop original column "fuel-type" from "df"

df.drop("fuel-type", axis = 1, inplace=True)

df.head()

EDA is an approach to analyze data in order to summarize the main characteristics of the data, gain better understanding of the data set, uncover relationships between different variables, and extract important variables for the problem we're trying to solve.

# ***load data and store in dataframe df***

# *final dataframe product after all the above treatment -- ready for analysis

path='https://s3-api.us-geo.objectstorage.softlayer.net/cf-courses-data/CognitiveClass/DA0101EN/automobileEDA.csv'

df = pd.read_csv(path)

i. Analyzing Individual Feature Patterns using Visualization

a. Continuous Numerical Variables

Continuous numerical variables may contain any value within some range. A great way to visualize these variables is by using scatterplots with fitted lines:

# import libraries

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pylab as plt

# correlation between: bore, stroke,compression-ratio, and horsepower

# df[["bore", "stroke", "compression-ratio", "horsepower"]].corr()

# Engine size as potential predictor variable of price

sns.regplot(x="engine-size", y="price", data=df)

plt.ylim(0,)

# correlation between 'engine-size' and 'price' is approximately 0.87:

df[["engine-size", "price"]].corr()

A Positive linear relationship is observed between engine size and price. The correlation between 'engine-size' and 'price' is approximately 0.87. The Engine size feature therefore seems like a pretty good predictor of price since the regression line is almost a perfect diagonal line

b. Categorical Variables

The categorical variables can have the type "object" or "int64". A good way to visualize categorical variables is by using boxplots.

- The distributions of price between the different body-style categories have a significant overlap, and so body-style would not be a good predictor of price:

# the relationship between "body-style" and "price"

sns.boxplot(x="body-style", y="price", data=df)

- The distribution of price between two engine-location categories -- front and rear, are distinct enough to take engine-location as a potentially good predictor of price

sns.boxplot(x="engine-location", y="price", data=df)

- The distribution of price between the different drive-wheels categories differs; as such drive-wheels could potentially be a predictor of price.

# drive-wheels

sns.boxplot(x="drive-wheels", y="price", data=df)

ii. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Value Counts

Note: the method value_counts only works on Pandas series, not Pandas Dataframes.

drive_wheels_counts = df['drive-wheels'].value_counts().to_frame()

drive_wheels_counts.rename(columns={'drive-wheels': 'value_counts'}, inplace=True)

# rename the index to 'drive-wheels'

drive_wheels_counts.index.name = 'drive-wheels'

drive_wheels_counts

iii. Basics of Grouping

Say we want to know, on average, which type of drive wheel is most valuable, we can group "drive-wheels" and then average them

# group by the variable "drive-wheels"

# df['drive-wheels'].unique()

# select columns

df_group_one = df[['drive-wheels','body-style','price']]

# calculate the average price for each of the different categories of data

df_group_one = df_group_one.groupby(['drive-wheels'],as_index=False).mean()

df_group_one

# You can also group with multiple variables

# group dataframe by the unique combinations 'drive-wheels' and 'body-style'

df_gptest = df[['drive-wheels','body-style','price']]

grouped_test1 = df_gptest.groupby(['drive-wheels','body-style'],as_index=False).mean()

grouped_test1

# grouped data is much easier to visualize when it is made into a pivot table

# A pivot table is like an Excel spreadsheet, with one variable along the column and another along the row

grouped_pivot = grouped_test1.pivot(index='drive-wheels',columns='body-style')

grouped_pivot

# fill missing values with 0

grouped_pivot = grouped_pivot.fillna(0)

grouped_pivot

# Let's use a heat map to visualize the relationship between Body Style vs Price

# The heatmap plots the target variable (price) proportional to colour with

# respect to the variables 'drive-wheel' and 'body-style' in the vertical and horizontal axis respectively

# This allows us to visualize how the price is related to 'drive-wheel' and 'body-style'.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

im = ax.pcolor(grouped_pivot, cmap='RdBu')

#label names

row_labels = grouped_pivot.columns.levels[1]

col_labels = grouped_pivot.index

#move ticks and labels to the center

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(grouped_pivot.shape[1]) + 0.5, minor=False)

ax.set_yticks(np.arange(grouped_pivot.shape[0]) + 0.5, minor=False)

#insert labels

ax.set_xticklabels(row_labels, minor=False)

ax.set_yticklabels(col_labels, minor=False)

#rotate label if too long

plt.xticks(rotation=90)

fig.colorbar(im)

plt.show()

iv. Correlation and Causation

Pearson Correlation

Pearson Correlation is the default method of the function corr. We can calculate the Pearson Correlation of 'int64' or 'float64' variables. The Pearson Correlation coefficient is a value between -1 and 1 inclusive, where:

- 1: Total positive linear correlation.

- 0: No linear correlation, the two variables most likely do not affect each other.

- -1: Total negative linear correlation.

P-value

The P-value tells us how certain we are about the correlation we calculated

Normally, we choose a significance level of 0.05, which means that we are 95% confident that the correlation between the

variables is significant. By convention, when the:

p-value is < 0.001:there is strong evidence that the correlation is significant.p-value is < 0.05:there is moderate evidence that the correlation is significant.p-value is < 0.1:there is weak evidence that the correlation is significant.p-value is > 0.1:there is no evidence that the correlation is significant.

# import libraries

from scipy import stats

# Horsepower vs Price

pearson_coef, p_value = stats.pearsonr(df['horsepower'], df['price'])

print("The Pearson Correlation Coefficient is", pearson_coef, " with a P-value of P = ", p_value)

Conclusion: Since the p-value is < 0.001, the correlation between horsepower and price is statistically significant, and the linear relationship is quite strong (~0.809, close to 1)

v. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

The ANOVA is a statistical method used to:

- test whether there are significant differences between the means of two or more groups.

- [It can be used to] find the correlation between different groups of a categorical variable.

F-test score: variation between sample group means divided by variation within sample group.

ANOVA assumes the means of all groups are the same, calculates how much the actual means deviate from the assumption, and reports it as the F-test score.

A larger score means there is a larger difference between the means.p-value: p-value, a.k.a. confidence degree a.k.a. Statistical significance tells how statistically significant our calculated score value is

Drive Wheels

Since ANOVA analyzes the difference between different groups of the same variable, the groupby function will come in handy. Let's see if different types 'drive-wheels' impact 'price'

# we group the data

# grouped_test2=df_gptest[['drive-wheels', 'price']].groupby(['drive-wheels'])

grouped_test2=df[['drive-wheels', 'price']].groupby(['drive-wheels'])

# obtain the values of the method group using the method "get_group".

grouped_test2.get_group('4wd')['price']

# use the function 'f_oneway' in the module 'stats' to obtain the F-test score and P-value.

f_val, p_val = stats.f_oneway(grouped_test2.get_group('fwd')['price'], grouped_test2.get_group('rwd')['price'], grouped_test2.get_group('4wd')['price'])

print( "ANOVA results: F=", f_val, ", P =", p_val)

This is a great result with a large F test score showing a strong correlation and a P value of almost 0 implying almost certain statistical significance.

# Separately: fwd and rwd

f_val, p_val = stats.f_oneway(grouped_test2.get_group('fwd')['price'], grouped_test2.get_group('rwd')['price'])

print( "ANOVA results: F=", f_val, ", P =", p_val )

# 4wd and rwd

f_val, p_val = stats.f_oneway(grouped_test2.get_group('4wd')['price'], grouped_test2.get_group('rwd')['price'])

print( "ANOVA results: F=", f_val, ", P =", p_val)

# 4wd and fwd

f_val, p_val = stats.f_oneway(grouped_test2.get_group('4wd')['price'], grouped_test2.get_group('fwd')['price'])

print("ANOVA results: F=", f_val, ", P =", p_val)

Conclusion: Important Variables

We now have a better idea of what our data looks like and which variables are important to take into account when predicting the car price. We have narrowed it down to the following variables:

| 1. Continuous numerical variables | 2. Categorical variables |

|---|---|

| Length | Drive-wheels |

| Width | |

| Curb-weight | |

| Engine-size | |

| Horsepower | |

| City-mpg | |

| Highway-mpg | |

| Wheel-base | |

| Bore |

As we now move into building machine learning models to automate our analysis, feeding the model with variables that meaningfully affect our target variable will improve our model's prediction performance.

# load data and store in dataframe df

path = 'https://s3-api.us-geo.objectstorage.softlayer.net/cf-courses-data/CognitiveClass/DA0101EN/automobileEDA.csv'

df = pd.read_csv(path)

df.head()

i. (Simple) Linear Regression

SLR helps us understand the relationship between 2 variables:

- The predictor/independent variable(x)

- The target/dependent variable (y)

The result of Linear Regression is a linear function that predicts the response/target/dependent variable as a function of the predictor/independent variable.

$$Linear function: Yhat = a + b X $$- a -- the intercept of the regression line; in other words: the value of Y when X is 0

- b -- the slope of the regression line, in other words: the value with which Y changes when X increases by 1 unit

How could Highway-mpg help us predict car price?

To find out, we will use simple linear regression to create a linear function with "highway-mpg" as the predictor variable and the "price" as the response variable.

# import libraries

# load the modules for linear regression

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

# definte the variables

X = df[['highway-mpg']]

Y = df['price']

# Create the linear regression object

lm = LinearRegression()

# Fit the linear model using highway-mpg

lm.fit(X,Y)

# What is the value of the intercept (a)?

lm.intercept_

# What is the value of the Slope (b)?

lm.coef_

ii. Multiple Linear Regression

Multiple Linear Regression is used to explain the relationship between one continuous dependent variable and two or more independent variables. Most real-world regression models involve multiple predictor/independent variables. We will illustrate the structure by using four predictor variables, but these results can generalize to any integer:

$$ Y: Response \ Variable\\ X_1 :Predictor\ Variable \ 1\\ X_2: Predictor\ Variable \ 2\\ X_3: Predictor\ Variable \ 3\\ X_4: Predictor\ Variable \ 4\\ $$$$ a: intercept\\ b_1 :coefficients \ of\ Variable \ 1\\ b_2: coefficients \ of\ Variable \ 2\\ b_3: coefficients \ of\ Variable \ 3\\ b_4: coefficients \ of\ Variable \ 4\\ $$$$ Yhat = a + b_1 X_1 + b_2 X_2 + b_3 X_3 + b_4 X_4 $$From the previous section we know that other good predictors of price could be:

- Horsepower

- Curb-weight

- Engine-size

- Highway-mpg

# develop a model using these variables as the predictor variables

Z = df[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg']]

# Fit the linear model using the four above-mentioned variables.

# lm.fit(Z, df['price'])

lm.fit(Z, Y)

# What is the value of the intercept(a)?

lm.intercept_

# What are the values of the coefficients (b1, b2, b3, b4)?

lm.coef_

What is the final estimated linear model that we get?

iii. Model Evaluation using Visualization

Now that we've developed some models, how do we evaluate our models and how do we choose the best one? One way to do this is by using visualization.

Regression Plot

This plot shows a combination of a scatter plot, as well as the fitted linear regression line going through the data. This will give us a reasonable estimate of:

- The relationship between the two variables

- the strength of the correlation

- the direction (positive or negative correlation)

# Horsepower as potential predictor variable of price

width = 12

height = 10

plt.figure(figsize=(width, height))

sns.regplot(x="highway-mpg", y="price", data=df)

plt.ylim(0,)

Pay attention to how scattered the data points are around the regression line. This will give you a good indication of the variance of the data, and whether a linear model would be the best fit or not. If the data is too far off from the line, this linear model might not be the best model for the data.

# peak-rpm" as potential predictor variable of price

plt.figure(figsize=(width, height))

sns.regplot(x="peak-rpm", y="price", data=df)

plt.ylim(0,)

Comparing the regression plot of "peak-rpm" and "highway-mpg" we see that the points for "highway-mpg" are much closer to the generated line and on the average decrease. The points for "peak-rpm" have more spread around the predicted line, and it is much harder to determine if the points are decreasing or increasing

df[["peak-rpm","highway-mpg","price"]].corr()

a. Residual Plot

The residual (e) is the difference between the observed value (y) and the predicted value (Yhat). When we look at a regression plot, the residual is the distance from the data point to the fitted regression line.

A residual plot is a graph that shows the residuals on the vertical y-axis and the independent variable on the horizontal axis

When looking at a residual plot, pay attention to the spread of the residuals:

- If the points are randomly spread out around the x-axis, then a linear model is appropriate for the data. Randomly spread out residuals means that the variance is constant, and thus the linear model is a good fit for this data.

In the residual plot below, the residuals are not randomly spread around the x-axis, which leads us to believe that maybe a non-linear model is more appropriate for this data.

plt.figure(figsize=(width, height))

sns.residplot(x=df['highway-mpg'], y=df['price'])

plt.show()

b. Distribution Plot

Visualizing a model for Multiple Linear Regression is a bit more complicated because you can't visualize it with a regression or residual plot.

One way to look at the fit of the model is by looking at the distribution plot.

We can look at the distribution of the fitted values that result from the model and compare it to the distribution of the actual values.

# First lets make a prediction

Y_hat = lm.predict(Z)

plt.figure(figsize=(width, height))

#kind{“hist”, “kde”, “ecdf”}

ax1 = sns.kdeplot(df['price'], color="r", label="Actual Value")

sns.kdeplot(Y_hat, color="b", label="Fitted Values" , ax=ax1)

plt.title('Actual vs Fitted Values for Price')

plt.xlabel('Price (in dollars)')

plt.ylabel('Proportion of Cars')

plt.show()

plt.close()

We can see that the fitted values are reasonably close to the actual values, since the two distributions overlap a bit. However, there is definitely some room for improvement.

iv. Polynomial Regression and Pipelines

Polynomial regression is a particular case of the simple linear regression model or multiple linear regression models.

We get non-linear relationships by squaring or setting higher-order terms of the predictor variables.

There are different orders of polynomial regression:

We saw earlier that a linear model did not provide the best fit while using highway-mpg as the predictor variable. Let's see if we can try fitting a polynomial model to the data instead. We will use the following function to plot the data:

def PlotPolly(model, independent_variable, dependent_variable, Name):

x_new = np.linspace(15, 55, 100)

y_new = model(x_new)

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12,12)

plt.plot(independent_variable, dependent_variable, '.', x_new, y_new, '-')

plt.title('Polynomial Fit with Matplotlib for Price ~ Length')

ax = plt.gca()

ax.set_facecolor((0.898, 0.898, 0.898))

fig = plt.gcf()

plt.xlabel(Name)

plt.ylabel('Price of Cars')

plt.show()

plt.close()

# get the variables

x = df['highway-mpg']

y = df['price']

# fit the polynomial using the function polyfit, then use the function poly1d to display the polynomial function.

# Here we use a polynomial of the 3rd order (cubic)

f = np.polyfit(x, y, 3)

p = np.poly1d(f)

print(p)

# plot the function

PlotPolly(p, x, y, 'highway-mpg')

We can already see from plotting that this polynomial model performs better than the linear model. This is because the generated polynomial function "hits" more of the data points.

The analytical expression for Multivariate Polynomial function gets complicated. For example, the expression for a second-order (degree=2) polynomial with two variables is given by: $$ Yhat = a + b_1 X_1 +b_2 X_2 +b_3 X_1 X_2+b_4 X_1^2+b_5 X_2^2 $$

We can perform a polynomial transform on multiple features (variables):

# import libraries

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

# create a PolynomialFeatures object of degree 2

pr=PolynomialFeatures(degree=2)

Z_pr=pr.fit_transform(Z)

In the original data, there are 201 samples and 4 features:

Z.shape

After the transformation, there are 201 samples and 15 features:

Z_pr.shape

Pipeline

Data Pipelines simplify the steps of processing the data.

from sklearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

Input=[('scale',StandardScaler()), ('polynomial', PolynomialFeatures(include_bias=False)), ('model',LinearRegression())]

pipe=Pipeline(Input)

pipe

Z = Z.astype(float)

pipe.fit(Z,y)

ypipe=pipe.predict(Z)

ypipe[0:3]

v. Measures for In-Sample Evaluation

When evaluating our models, not only do we want to visualize the results, we also want a quantitative measure of it

Two very important measures often used in Statistics are:

A measure to indicate how close the data is to the fitted regression line.

The value of the R-squared is the percentage of variation of the response variable (y) that is explained by a linear model

MSE measures the average of the squares of errors -- that is, the difference between actual value (y) and the estimated value (ŷ).

Model 1: Simple Linear Regression

R^2:

# highway_mpg_fit

lm.fit(X, Y)

print('The R-square is: ', lm.score(X, Y))

We can say that ~49.659% of the variation of the price is explained by this simple linear model "horsepower_fit".

MSE:

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

# predict the output

Yhat=lm.predict(X)

# print('The output of the first four predicted value is: ', Yhat[0:4])

# compare the predicted results with the actual results

mse = mean_squared_error(df['price'], Yhat)

print('The mean square error of price and predicted value is: ', mse)

Model 2: Multiple Linear Regression

R^2:

# fit the model

lm.fit(Z, df['price'])

# Find the R^2

print('The R-square is: ', lm.score(Z, df['price']))

We can say that ~80.896 % of the variation of price is explained by this multiple linear regression "multi_fit".

MSE:

# produce a prediction

Y_predict_multifit = lm.predict(Z)

# compare the predicted results with the actual results

print('The mean square error of price and predicted value using multifit is: ', \

mean_squared_error(df['price'], Y_predict_multifit))

Model 3: Polynomial Fit

R^2:

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score

r_squared = r2_score(y, p(x))

print('The R-square value is: ', r_squared)

We can say that ~67.419 % of the variation of price is explained by this polynomial fit.

MSE:

mean_squared_error(df['price'], p(x))

vi. Prediction and Decision Making

a. Prediction

In the previous section, we trained the model using the method fit.

Now we will use the method predict to produce a prediction.

new_input=np.arange(1, 100, 1).reshape(-1, 1)

# Fit the model:

lm.fit(X.values, Y)

# Produce a prediction

yhat=lm.predict(new_input)

yhat[0:3]

# plot the data

plt.plot(new_input, yhat)

plt.show()

b. Decision Making: Determining a Good Model Fit

Now that we have visualized the different models, and generated the R-squared and MSE values for the fits, how do we determine a good model fit?

- What is a good R-squared value? -- Models with higher R-squared values are better fits for data

- What is a good MSE? -- Models with smaller MSE values are better fits for data

Conclusion

Comparing the SLR, MLR amd Polynimial regression models, we conclude that the MLR model is the best model for predicting price from our dataset. This result makes sense since we have 27 variables in total and we know that more than one of those variables is a potential predictor of the final car price.

We have built models and made predictions (of vehicle prices). Now we will determine how accurate these predictions are

# Import clean data

path = 'https://s3-api.us-geo.objectstorage.softlayer.net/cf-courses-data/CognitiveClass/DA0101EN/module_5_auto.csv'

df = pd.read_csv(path)

# First lets only use numeric data

df=df._get_numeric_data()

df.head()

# Libraries for plotting

from IPython.display import display

from ipywidgets import interact, interactive, fixed, interact_manual, widgets

# Functions for plotting

def DistributionPlot(RedFunction, BlueFunction, RedName, BlueName, Title):

width = 12

height = 10

plt.figure(figsize=(width, height))

# ax1 = sns.distplot(RedFunction, hist=False, color="r", label=RedName)

# ax2 = sns.distplot(BlueFunction, hist=False, color="b", label=BlueName, ax=ax1)

ax1 = sns.kdeplot(RedFunction, color="r", label=RedName)

ax2 = sns.kdeplot(BlueFunction, color="b", label=BlueName, ax=ax1)

plt.title(Title)

plt.xlabel('Price (in dollars)')

plt.ylabel('Proportion of Cars')

plt.show()

plt.close()

def PollyPlot(xtrain, xtest, y_train, y_test, lr,poly_transform):

width = 12

height = 10

plt.figure(figsize=(width, height))

xmax=max([xtrain.values.max(), xtest.values.max()])

xmin=min([xtrain.values.min(), xtest.values.min()])

x=np.arange(xmin, xmax, 0.1)

plt.plot(xtrain, y_train, 'ro', label='Training Data')

plt.plot(xtest, y_test, 'go', label='Test Data')

plt.plot(x, lr.predict(poly_transform.fit_transform(x.reshape(-1, 1))), label='Predicted Function')

plt.ylim([-10000, 60000])

plt.ylabel('Price')

plt.legend()

i. Training and Testing

An important step in testing your model is to split your data into training and testing data.

R^2

# place the target data price in a separate dataframe y:

y_data = df['price']

# drop price data in x data

x_data=df.drop('price',axis=1)

# x_data.head()

# Now we randomly split our data into training and testing data using the function train_test_split

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# split up the data set such that 15% of the data samples will be used for testing

x_train, x_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(x_data, y_data, test_size=0.15, random_state=1)

#y_train = a + b(x_train)

#y_hat = a + b(x_test)

#lre.score below creates/predicsts y_hat and compares it with y_test and gives a score

print("number of test samples :", x_test.shape[0])

print("number of training samples:",x_train.shape[0])

# import LinearRegression

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

# create a Linear Regression object

lre=LinearRegression()

# fit the model using the feature horsepower

lre.fit(x_train[['horsepower']], y_train)

# Calculate the R^2 on the test data

lre.score(x_test[['horsepower']], y_test)

lre.score(x_train[['horsepower']], y_train)

Cross-validation Score

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

# Calculate the average R^2 using four folds, and 'horsepower' as a feature

# We input the object, the feature in this case ' horsepower', the target data (y_data).

# The parameter 'cv' determines the number of folds; in this case 4.

# The default scoring is R^2; each element in the array has the average R^2 value in the fold

Rcross = cross_val_score(lre, x_data[['horsepower']], y_data, cv=4)

Rcross

# calculate the average and standard deviation of our estimate(Rcross):

print("The mean of the folds are", Rcross.mean(), "and the standard deviation is" , Rcross.std())

Negative Squared Error

-1 * cross_val_score(lre,x_data[['horsepower']], y_data,cv=4,scoring='neg_mean_squared_error')

You can also use the function 'cross_val_predict' to predict the output. The function splits up the data into the specified number of folds, using one fold to get a prediction while the rest of the folds are used as test data.

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_predict

# We input the object, the feature in this case 'horsepower' , the target data y_data.

# The parameter 'cv' determines the number of folds; in this case 4. We can produce an output:

yhat = cross_val_predict(lre,x_data[['horsepower']], y_data,cv=4)

yhat[0:5]

ii. Overfitting

- Overfitting occurs when the model fits the noise, not the underlying process.

- Note: The test data -- sometimes referred to as the out of sample data -- is a much better measure of how well your model performs in the real world:

# create Multiple linear regression object

lr = LinearRegression()

# train the model using 'horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size' and 'highway-mpg' as features.

lr.fit(x_train[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg']], y_train)

# Prediction using training data:

yhat_train = lr.predict(x_train[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg']])

yhat_train[0:5]

# Prediction using test data:

yhat_test = lr.predict(x_test[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg']])

yhat_test[0:5]

Let's perform some model evaluation using our training and testing data separately

# import the seaborn and matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# examine the distribution of the predicted values of the training data.

plt.figure(figsize=(width, height))

ax1 = sns.kdeplot(y_train, color="r", label="Actual Values (Train)")

sns.kdeplot(yhat_train, color="b", label = "Predicted Values (Train)", legend=True, ax=ax1)

plt.title('Distribution Plot of Predicted Value Using Training Data vs Training Data Distribution')

plt.xlabel('Price (in dollars)')

plt.ylabel('Proportion of Cars')

plt.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.05, 1), loc=2, borderaxespad=0.)

plt.show()

plt.close()

Figure 1: Plot of predicted values using the training data compared to the training data.

So far the model seems to be doing well in learning from the training dataset. But what happens when the model encounters new data from the testing dataset? When the model generates new values from the test data, we see the distribution of the predicted values is much different from the actual target values.

# import the seaborn and matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# examine the distribution of the predicted values of the training data.

plt.figure(figsize=(width, height))

ax1 = sns.kdeplot(y_test, color="r", label="Actual Values (Test)")

sns.kdeplot(yhat_test, color="b", label = "Predicted Values (Test)", legend=True, ax=ax1)

plt.title('Distribution Plot of Predicted Value Using Test Data vs Data Distribution of Test Data')

plt.xlabel('Price (in dollars)')

plt.ylabel('Proportion of Cars')

plt.legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.05, 1), loc=2, borderaxespad=0.)

plt.show()

plt.close()

Figure 2: Plot of predicted value using the test data compared to the test data.

Comparing Figure 1 and Figure 2, it is evident that the distribution of the test data in Figure 1 is much better at fitting the data. This difference in Figure 2 is apparent where the ranges are from 5000 to 15 000. This is where the distribution shape is exceptionally different. Let's see if polynomial regression also exhibits a drop in the prediction accuracy when analysing the test dataset.

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

x_train, x_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(x_data, y_data, test_size=0.45, random_state=0)

# We will perform a degree 5 polynomial transformation on the feature 'horse power'

pr = PolynomialFeatures(degree=5)

x_train_pr = pr.fit_transform(x_train[['horsepower']])

x_test_pr = pr.fit_transform(x_test[['horsepower']])

pr

# create a linear regression model "poly" and train it

poly = LinearRegression()

poly.fit(x_train_pr, y_train)

# We can see the output of our model using the method "predict." then assign the values to "yhat"

yhat = poly.predict(x_test_pr)

# Let's take the first five predicted values and compare it to the actual targets.

print("Predicted values:", yhat[0:4])

print("True values:", y_test[0:4].values)

# use the function "PollyPlot" that we defined at the beginning of the lab

# to display the training data, testing data, and the predicted function.

PollyPlot(x_train[['horsepower']], x_test[['horsepower']], y_train, y_test, poly,pr)

Figure 4 A polynomial regression model. Red dots represent training data, green dots represent test data, and the blue line represents the model prediction.

We see that the estimated function appears to track the data but around 200 horsepower, the function begins to diverge from the data points.

R^2 of the training data:

poly.score(x_train_pr, y_train)

R^2 of the test data:

poly.score(x_test_pr, y_test)

We see the R^2 for the training data is 0.5567 while the R^2 on the test data was -29.87. The lower the R^2, the worse the model, a Negative R^2 is a sign of overfitting. Let's see how the R^2 changes on the test data for different order polynomials and plot the results:

Rsqu_test = []

order = [1, 2, 3, 4]

for n in order:

pr = PolynomialFeatures(degree=n)

x_train_pr = pr.fit_transform(x_train[['horsepower']])

x_test_pr = pr.fit_transform(x_test[['horsepower']])

lr.fit(x_train_pr, y_train)

Rsqu_test.append(lr.score(x_test_pr, y_test))

plt.plot(order, Rsqu_test)

plt.xlabel('order')

plt.ylabel('R^2')

plt.title('R^2 Using Test Data')

plt.text(3, 0.75, 'Maximum R^2 ')

We see the R^2 gradually increases until an order three polynomial is used. Then the R^2 dramatically decreases at four.

def f(order, test_data):

x_train, x_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(x_data, y_data, test_size=test_data, random_state=0)

pr = PolynomialFeatures(degree=order)

x_train_pr = pr.fit_transform(x_train[['horsepower']])

x_test_pr = pr.fit_transform(x_test[['horsepower']])

poly = LinearRegression()

poly.fit(x_train_pr,y_train)

PollyPlot(x_train[['horsepower']], x_test[['horsepower']], y_train,y_test, poly, pr)

The following interface allows you to experiment with different polynomial orders and different amounts of data.

interact(f, order=(0, 6, 1), test_data=(0.05, 0.95, 0.05))

Polynomial transformations with more than one feature

# Create a "PolynomialFeatures" object "pr1" of degree two

pr1=PolynomialFeatures(degree=2)

# Transform the training and testing samples for the features 'horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size' and 'highway-mpg'

x_train_pr1=pr.fit_transform(x_train[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg']])

x_test_pr1=pr.fit_transform(x_test[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg']])

How many dimensions does the new feature have? Hint: use the attribute "shape"

x_train_pr1.shape

# There are now 15 features:

# Create a linear regression model "poly1" and train the object using the method "fit" using the polynomial features

poly1=LinearRegression().fit(x_train_pr1,y_train)

# predict an output on the polynomial features

yhat_test1=poly1.predict(x_test_pr1)

# display the distribution of the predicted output vs the test data

Title='Distribution Plot of Predicted Value Using Test Data vs Data Distribution of Test Data'

DistributionPlot(y_test, yhat_test1, "Actual Values (Test)", "Predicted Values (Test)", Title)

# perform a degree two polynomial transformation on our data

# NB: our test data will be used as validation data

pr=PolynomialFeatures(degree=2)

x_train_pr=pr.fit_transform(x_train[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg','normalized-losses','symboling']])

x_test_pr=pr.fit_transform(x_test[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg','normalized-losses','symboling']])

# import Ridge

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

# create a Ridge regression object, setting the regularization parameter to 0.1

# create a Ridge regression object, setting the regularization parameter to 0.2

RigeModel=Ridge(alpha=0.2)

# fit the model

RigeModel.fit(x_train_pr, y_train)

# obtain a prediction

yhat = RigeModel.predict(x_test_pr)

# compare the first five predicted samples to our test set

print('predicted:', yhat[0:4])

print('test set :', y_test[0:4].values)

# We select the value of Alfa that minimizes the test error, for example, we can use a for loop.

Rsqu_test = []

Rsqu_train = []

dummy1 = []

ALFA = 10 * np.array(range(0,1000))

for alfa in ALFA:

RigeModel = Ridge(alpha=alfa)

RigeModel.fit(x_train_pr, y_train)

Rsqu_test.append(RigeModel.score(x_test_pr, y_test))

Rsqu_train.append(RigeModel.score(x_train_pr, y_train))

# plot out the value of R^2 for different Alphas

width = 12

height = 10

plt.figure(figsize=(width, height))

plt.plot(ALFA,Rsqu_test, label='validation data ')

plt.plot(ALFA,Rsqu_train, 'r', label='training Data ')

plt.xlabel('alpha')

plt.ylabel('R^2')

plt.legend()

Figure 6:The blue line represents the R^2 of the test data, and the red line represents the R^2 of the training data. The x-axis represents the different values of Alfa. The red line in figure 6 represents the R^2 of the test data, as Alpha increases the R^2 decreases; therefore as Alfa increases the model performs worse on the test data. The blue line represents the R^2 on the validation data, as the value for Alfa increases the R^2 decreases.

Task 4):

Perform Ridge regression and calculate the R^2 using the polynomial features, use the training data to train the model and test data to test the model. The parameter alpha should be set to 10.RigeModel = Ridge(alpha=0)

RigeModel.fit(x_train_pr, y_train)

RigeModel.score(x_test_pr, y_test)

# import GridSearchCV

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

# We create a dictionary of parameter values

parameters1= [{'alpha': [0.001,0.1,1, 10, 100, 1000, 10000, 100000, 100000]}]

parameters1

# Create a ridge regions object

RR=Ridge()

RR

# Create a ridge grid search object

Grid1 = GridSearchCV(RR, parameters1,cv=4)

# Fit the model

Grid1.fit(x_data[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg']], y_data)

The object finds the best parameter values on the validation data. We can obtain the estimator with the best parameters and assign it to the variable BestRR as follows:

BestRR=Grid1.best_estimator_

BestRR

# test our model on the test data

BestRR.score(x_test[['horsepower', 'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'highway-mpg']], y_test)